|

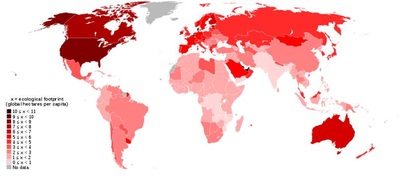

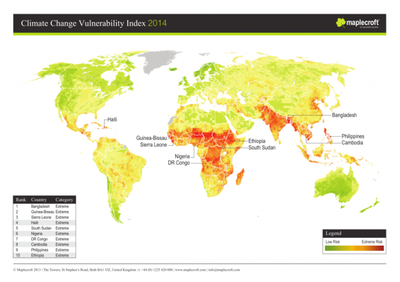

I do a lot of work with a grassroots group called Climate Justice Montreal. I’m pretty sure most people have never heard of the idea of climate justice, but it’s basically the concept that the individuals and countries are most responsible for greenhouse gas emissions generally are the least likely to be affected by global warming impacts. Those who are most effected by droughts, floods, displacement, sea level rise, heat waves, shifting biodiversity, etc, are those in the world who are already vulnerable - usually those in the global south or communities of color in Western countries. When I do presentations about climate justice, I always show these two maps because I think it shows things very simply. You'll notice that the countries that use the most natural resources are the least likely to be affected by climate change impacts.  I think about “climate injustice” a lot, but I rarely am able to experience it at any concrete way. Sometimes climate injustice feels like just far away definition, some sad yet unsurprising news when vulnerable communities devastated by extreme weather or food shortages caused by climate change. I’ve had pretty opposite examples of climate injustice this summer. The first was in July, when I spent a week in Haiti working on some community projects with a small non-profit. I went to Haiti not necessarily under the rationale that I would be helping people (although I was), but I went as a learning experience. I went with a small organization called To Love a Child, who I found through my Mom's involvement with them. Weeks before the trip, I was so anxious that I could barely sleep. Why was I deliberately going to a very impoverished country, with plenty of tropical diseases, "rustic" amenities at best, to supposedly help people I had never met before? In a country plagued with political and natural resource problems, stemming from a colonized and oppressive history, how could I be sure that I was actually contributing to a real solution, instead of just being a well-off white girl imposing her values and culture on others? How could I really know that what I was doing was meaningful? I found myself in a beautiful little village. My profession is teaching environmental science and coordinating sustainability projects; in my free time I work with Climate Justice Montreal to put on events and workshops educating and mobilizing people about climate change. It's easy to get discouraged, and it's easy sometimes to drown in the perpetually bad news. But here, in the village, things seemed calm. People seemed genuinely content; they had a strong connection to their faith and community. Kids shared things with each other without being told, adults watched out for kids that weren't their own. Since many people were unemployed, they had time to sit around and talk and laugh with each other. Instead of all being on our individual cell phones or laptops, there was nothing to do in the evening but play games with the local kids and chat. Chickens strutted through my bedroom and settled on my pillow. There were no distractions; everyone was present, doing exactly what they were supposed to be doing. I guess I was expecting everything to be depressed or depressing, but I didn't find that at all. Instead, I felt sad for the people back home – normal people, maybe like you and sometimes me, working 60 hour weeks, uncomfortable when the wifi's down, feeling completely empty the second they finally notice the crushing loneliness that surrounds them. I expected to be struck by the destitution of the situation, but I found its issues more nuanced. At first in the village, I noticed the garbage, since it's the most obvious. There's no garbage removal services or any real alternative to littering or burning it, and plastic is forever. Then I noticed the lack of freshwater. People bathed in the river and if lucky they had a latrine; if they wanted water they would have to carry it on their head in buckets long distances up the mountains. Okay, garbage, freshwater, these are problems. Also the heat - it was the dry season, and it was scorching the crops. The ground was hilly, often eroded and infertile. People lived on small plots around the mountains and survived off of subsistence farming. There wasn't a grocery store, or a corner store to buy food in town - it required a vehicle, which many people in the village didn't have. That would require money, and how could people afford such an expense? Most people lived in simple wooden huts with tin roofs, and their whole family lived in a space the size of my bedroom back home.  Pollution, scarcity of water, infertility of the soil, drought, food insecurity, lack of medical care. No running water or electricity. Families often couldn't afford to send their children to primary or secondary school; most of the people in the village were illiterate. Despite its serenity, this is a vulnerable place. As hard as it was for me to imagine how people currently manage to acquire the basics necessary for daily survival, it suddenly hit me - this is climate injustice. Before my trip, I had been curious to ask Haitians their view on climate change. But I found myself unable to bring it up when I was there, even with the people my age that I befriended. I didn’t know how to bring it up. “So...by the way, how do you feel about the world getting hotter, which will inevitably make conditions a whole lot tougher around here?” I had a hard time imagining the studies I had read back home about how the temperatures in tropical regions would drastically increase in the next few decades. It just didn’t seem real. It was nearly impossible to comprehend how things might get significantly worse for the people here who already struggled for daily necessities. As we sang Hallelujah in the makeshift wooden church, wide-eyed little girls in their Sunday best turned around to stare at us, and I blinked away my tears. It was so incredibly unfair. I expected to be culture shocked when I got back from Haiti. Actually, I had prepared myself for a week of feeling terribly sad about what I had just witnessed. I felt really strange on the way back home- like I had just glimpsed a completely different, unbelievable world, yet I knew that I would be unable to articulate to everyone back home what it was really like. But, like most humans, I adjusted pretty fast. I made it back to my apartment, snuggled into my own bed, and life went back normal. After a few weeks, it was like I hadn’t gone at all.

Glacier National Park Glacier National Park I was surprised by just how absolutely massive the boat was – there were three bars, two theatres, four hot tubs, two pools, a spa, a gym, and a whole bunch of free restaurants. My bed was magically remade when I entered my room in the evening, with a little chocolate resting on my pillow. Sometimes it felt like being at summer camp, with evening activities led by an animator brimming with fake enthusiasm. When each activity came to a close, the next logical way to pass time was to go back to the buffet. Eating copious amounts of food was a serious, continual event on the cruise, and it felt like being handed the keys to a candy store. When our boat docked in Juneau, I had some time to walk around town by myself. The coastal towns in Alaska are small, packed with tourist shops and tour companies – grizzly viewing, whale watching, ziplines, train rides. Most of the salespeople and tour guides were seasonal workers from out of state. On my walk, I passed bright jewellery stores and tacky souvenir shops. Most of the windows displayed Native-inspired potholders, key chains, tshirts, postcards, every possible cheesy thing. I was looking for something more authentic, a shop with stuff made by local people that were paid fairly for their work. Something more respectful of the culture than cheap make your own moccasin kits and “Alaskan Native friend” dolls with fur trim and big pretty eyes. Uninterested, I kept walking through the crowed, rainy streets. I passed a small community center nestled in the shops. And as I glanced in the window, I saw a packed room of mostly Indigenous folks eating dinner. I noticed the emergency soup kitchen sign in the window. I paused to look around at the town – the village was flooded literally thousands of mostly white, overfed tourists, seeking a souvenir of a frontier fantasy or curio of Native Alaska, and here were a room full of people presumably actually from the area, invisibly eating at a soup kitchen. When the tourist season ends soon, the wealthy shopkeepers will close their doors, the guides will fly back home, and the boats in harbour won’t dump hordes of visitors into the town. I’m pretty sure the soup kitchen will still be open. The next day, the cruise ship was heading up through Glacier National Park, so we were asked to be extra careful not to let litter blow overboard. I contained my inner sarcasm, something about how out of all of the steps we could take to preserve the pristine Arctic, maybe could we please not litter? I felt a surreal disconnect of being on a boat whose sole purpose is to help people over-consume in the name of pleasure, watching melting glaciers calve off into the ocean as hundreds of people stare out windows with their cameras. Literally perpetuating and documenting our demise. Wait, let me take a selfie. I thought to back to the month before, the conversations I had in French with the Haitians I met during my trip. It seemed like it would be kind of funny to the trade situations of one of the rich women on the boat with one of the women I met in the village. It would be hilarious... if it wasn’t so absurd that it’s even possible that two humans living on the same planet can have such diametrically opposite realities. To be on a monstrous cruise boat, the epitome of consumption, grazing our way to a National Park to watch climate change melt the glaciers into the sea – isn’t this the American Dream? I hesitate to say that most of the tourists on the boat are immune to climate change impacts, but we’re definitely insulated. And this is climate injustice.

2 Comments

10/1/2014 01:23:37 pm

This is a lovely and thoughtful post. I like the juxtaposition you've made. I think the point about the pace of life in Haiti and how monetary "poverty" and misery are not necessarily equivalent is an important one to consider more fully. Have you looked into projects like Bhutan's "Gross National Happiness" index, and other places where indigenous traditions are being valued in ways that dodge some of the traps placed by economic modernization and globalization?

Reply

Shona

10/15/2014 01:42:49 am

Thanks for reading, Michelle! I've heard of the Gross National Happiness index but I haven't looked into it that thoroughly. It seems like a great idea!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About ShonaI'm an eco-conscious girl from Montreal, Quebec. I'm currently an adjunct science professor at Champlain College of Vermont (Montreal Campus). I'm interested in any opportunities to expand my experience with grassroots activism, climate change legislation, or environmental education. Archives

March 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed