|

Students across Canada sleep outside for 5 nights without food, water, or hygiene products to raise money for organizations that support homelessness.

I slept one night on the streets of Montreal with the 5 Days for the HomelessConcordia University team. A couple things stuck with me from this meaningful experience:

Normally I totally avoid disposable products, but there was no way I was going to ask a random person to please rinse out my reusable mug before they bought me a coffee. 2. It’s encouraging to get a smile. Even if people didn’t donate, a little respect can go a long way. After so many people ignoring us, it was nice for someone to finally acknowledge that we were talking to them. 3. On the street, it’s hard to focus on anything besides the present moment. I didn’t have access to my phone or computer, so I couldn’t get any work done that evening. Instead, I watched people, talked with others, or enjoyed a warm hot chocolate. Sleeping on the sidewalk ended up being super uncomfortable, but thanks to a security guard, at least I knew that I (and my stuff) would be safe. I was able to get a few hours of sleep in, but it was still very hard to focus and actually be productive at work. I looked (and smelled) unprofessional. 4. People are freaking generous, but we definitely have privilege. I was so surprised and touched at how people donated their time and money, and went out of their way to get us food. However, I couldn’t help thinking that we were part of a group of students, on campus, who had some recognition already from our peers and the media. When actual people on the streets came by to hang out with us, bystanders were less friendly or even avoided them completely, compared to how they treated our team wearing bright orange shirts. Hopefully people are as generous to actual homeless folks, but I think our privilege made us feel a greater acceptance and support from the general public who walked by. 5. There are tons of ways to volunteer to help homelessness There are so many ways to help combat poverty and hunger. The funds we raised went to Chez Doris and Dans la Rue, but there many more community groups that help. We met homeless folks who told us about their mental illness, addiction problems, and getting jumped by other people on the street. Taking the time to get involved at a shelter, soup kitchen, fundraiser, or even using your professional skills can be a win-win for the community and your soul. A good start to understanding homelessness is to take the time to learn about the connection between poverty, racism, and health (hint: it’s a little more complicated than just “get a job”). My night with 5 Days for the Homeless was a really rewarding and surprisingly fun experience! Most of my professional and personal life is spent working on community engagement and social/environmental justice, but it was so rejuvenating to actually be outside and experience people’s generosity and struggles first hand. Although I’m a tourist to this situation and actual people on the streets have so much stacked against them, I hope this has helped to raise awareness and funds for community organizations that help those in need.

0 Comments

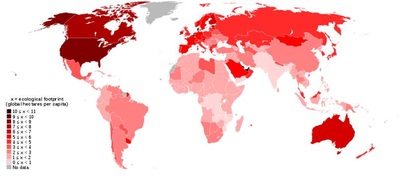

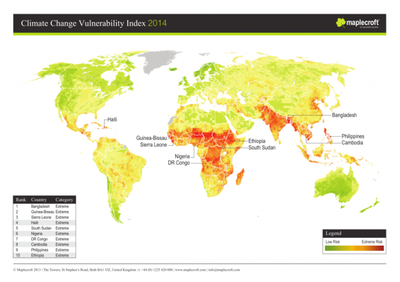

It’s not that we can’t admit the reality of climate change…it’s that we can’t even comprehend.5/15/2015  I've been spending a lot of time lately at my cottage. For the past few months, I've been super busy with contract work, and it’s been hard to find a time to settle down. Now that I have some free time, I've escaped to the country. My thoughts have started to slow and the days are getting longer. A colleague recently posted this article about how climate models are using increasingly unrealistic assumptions that we will get our act together to prevent 2C degree warming. The article concludes that no one wants to admit the scientific reality that it’s basically impossible that we will actually avoid catastrophic changes. It’s a tough read, and not just because it uses a bunch of acronyms and data. When I read articles about climate change, sometimes I feel a jolt. I see a disconnect between the normalcy of our daily lives and the urgency of acting, even with my friends in the scientific/activism community. Even for people who are such believers in science, who trust the “facts” and data, it seems almost impossible for us to believe that life will be drastically different in the future. We are starving for optimism. When I tell my peers about my thoughts on inevitable climate damages and injustices, the response is often “well, we don’t know for sure that it will be that bad”, “there’s still time” and “don’t be an alarmist”. I settle into a feeling of comfort that maybe I am being too pessimistic. Maybe it will all be okay somehow. Maybe we will figure it out. It’s nicer to think that way. Yesterday, a very close friend’s grandfather died peacefully. After hearing the news, I walked through the woods before sunset, listening to the haunting calls of hermit thrushes and searching for wild leek. The shadows were deepening during my walk, and my feet sank into the soft ground. My friend called to talk about her loss. I sat on a mossy rock and we had the type of conversation you have when you realize again how fragile it all is. Looking around while we chatted, I noticed everything is changing so quickly and slowly. The jack in the pulpits are out, and all of the wild strawberries are in bloom within just a few days. When I think about climate change, it’s easy to see it as headlines in a place far away. It’s getting more palpable, for sure, like Quebec’s record cold winter and my extra high heating bills. But it’s still so slow, so piecemeal and so far away. Something bad is happening in the arctic. Something bad is happening with climate refugees. Something bad is happening on the other coast. There will be another international conference, we will be skeptically hopeful, the activists will rally, and we will sigh and try again for next year.  A big part of the climate justice movement is about building a better community. By learning how to make decisions more collectively, by taking the time to build relationships, to eat meals together, to grow our own food, to acknowledge our histories, to become more mindful, to honor the places we live in. But here, with the blue jays calling outside, with the bees bringing back their last pollen of the day, with the warm breeze…it’s hard to actually feel that the world is slowly dying. Sometimes I can’t wrap my head around the distance between present moments drenched in beauty and future projections aching with grief. How do other people deal with this dissonance?  Katie and I together in a rare but blissful occasion Katie and I together in a rare but blissful occasion Over the holidays, my best friend Katie was in town and I got to spend TWO WHOLE DAYS with her. This is a big deal because for the past few years, she’s lived in on the west coast so Shona/Katie times are too far and few between. Katie has been my best friend for nearly 10 years, since we met on the first day of Freshman orientation at McGill. (he was from New York State, I was from New York State, and neither of us was into the debaucherous frosh week...aaaaand our friendship was forever sealed.) When Katie and I get to spend the day together, there’s always some existentialist questions that we need to confer with each other. Whether it’s the fate of a relationship, confusion about jobs, or frustrations with the people around us, we usually have some pretty intense conversations. Katie is the friend who will tell me when my bad ideas are terrible, ask me the questions I don’t want to ask myself, and be my biggest supporter to follow my dreams. I can confidently say that she has influenced several of my big life decisions, including...suggesting to start my own sustainability consulting business! (thanks, Katie!) So when she sent me an article about us both independently doing a Life Audit, I knew I should listen. Her friend Ximena Vengoechea had written a great article on How and Why to do a Life Audit, which is basically brainstorming your goals and seeing if they match up with what you are currently working toward. I would highly recommend the article – check it out! It took me a few hours, but I settled in with some tea, turned up the heat in my very chilly apartment, and I began to audit my life. First, you’re supposed to take a stack of Post-It notes and write a goal on each one until you get to 100. According to the article, most people can come up with around 30-40, and the author came up with 121. I thought that coming up with 100 would be easy for me since generally there are lots of things I want to do in life. And I wanted to think of more than 121 because...well I don’t know why, I guess I was just being competitive. (I know, trying to compete with someone you’ve never met about who can think of more life goals is totally ridiculous. One of my goals is not to compare myself to others as much). I came up with 60 goals. I could have made more small goals or more lofty goals, but I figured unrealistic ones like “become fabulously wealthy” and “stop climate change” are not that useful for the purpose of this exercise. My bed ended up covered in Post-Its. I do a lot of work with a grassroots group called Climate Justice Montreal. I’m pretty sure most people have never heard of the idea of climate justice, but it’s basically the concept that the individuals and countries are most responsible for greenhouse gas emissions generally are the least likely to be affected by global warming impacts. Those who are most effected by droughts, floods, displacement, sea level rise, heat waves, shifting biodiversity, etc, are those in the world who are already vulnerable - usually those in the global south or communities of color in Western countries. When I do presentations about climate justice, I always show these two maps because I think it shows things very simply. You'll notice that the countries that use the most natural resources are the least likely to be affected by climate change impacts.  I think about “climate injustice” a lot, but I rarely am able to experience it at any concrete way. Sometimes climate injustice feels like just far away definition, some sad yet unsurprising news when vulnerable communities devastated by extreme weather or food shortages caused by climate change. I’ve had pretty opposite examples of climate injustice this summer. The first was in July, when I spent a week in Haiti working on some community projects with a small non-profit. I went to Haiti not necessarily under the rationale that I would be helping people (although I was), but I went as a learning experience. I went with a small organization called To Love a Child, who I found through my Mom's involvement with them. Weeks before the trip, I was so anxious that I could barely sleep. Why was I deliberately going to a very impoverished country, with plenty of tropical diseases, "rustic" amenities at best, to supposedly help people I had never met before? In a country plagued with political and natural resource problems, stemming from a colonized and oppressive history, how could I be sure that I was actually contributing to a real solution, instead of just being a well-off white girl imposing her values and culture on others? How could I really know that what I was doing was meaningful? I found myself in a beautiful little village. My profession is teaching environmental science and coordinating sustainability projects; in my free time I work with Climate Justice Montreal to put on events and workshops educating and mobilizing people about climate change. It's easy to get discouraged, and it's easy sometimes to drown in the perpetually bad news. But here, in the village, things seemed calm. People seemed genuinely content; they had a strong connection to their faith and community. Kids shared things with each other without being told, adults watched out for kids that weren't their own. Since many people were unemployed, they had time to sit around and talk and laugh with each other. Instead of all being on our individual cell phones or laptops, there was nothing to do in the evening but play games with the local kids and chat. Chickens strutted through my bedroom and settled on my pillow. There were no distractions; everyone was present, doing exactly what they were supposed to be doing. I guess I was expecting everything to be depressed or depressing, but I didn't find that at all. Instead, I felt sad for the people back home – normal people, maybe like you and sometimes me, working 60 hour weeks, uncomfortable when the wifi's down, feeling completely empty the second they finally notice the crushing loneliness that surrounds them. I expected to be struck by the destitution of the situation, but I found its issues more nuanced. At first in the village, I noticed the garbage, since it's the most obvious. There's no garbage removal services or any real alternative to littering or burning it, and plastic is forever. Then I noticed the lack of freshwater. People bathed in the river and if lucky they had a latrine; if they wanted water they would have to carry it on their head in buckets long distances up the mountains. Okay, garbage, freshwater, these are problems. Also the heat - it was the dry season, and it was scorching the crops. The ground was hilly, often eroded and infertile. People lived on small plots around the mountains and survived off of subsistence farming. There wasn't a grocery store, or a corner store to buy food in town - it required a vehicle, which many people in the village didn't have. That would require money, and how could people afford such an expense? Most people lived in simple wooden huts with tin roofs, and their whole family lived in a space the size of my bedroom back home.  Pollution, scarcity of water, infertility of the soil, drought, food insecurity, lack of medical care. No running water or electricity. Families often couldn't afford to send their children to primary or secondary school; most of the people in the village were illiterate. Despite its serenity, this is a vulnerable place. As hard as it was for me to imagine how people currently manage to acquire the basics necessary for daily survival, it suddenly hit me - this is climate injustice. Before my trip, I had been curious to ask Haitians their view on climate change. But I found myself unable to bring it up when I was there, even with the people my age that I befriended. I didn’t know how to bring it up. “So...by the way, how do you feel about the world getting hotter, which will inevitably make conditions a whole lot tougher around here?” I had a hard time imagining the studies I had read back home about how the temperatures in tropical regions would drastically increase in the next few decades. It just didn’t seem real. It was nearly impossible to comprehend how things might get significantly worse for the people here who already struggled for daily necessities. As we sang Hallelujah in the makeshift wooden church, wide-eyed little girls in their Sunday best turned around to stare at us, and I blinked away my tears. It was so incredibly unfair. I expected to be culture shocked when I got back from Haiti. Actually, I had prepared myself for a week of feeling terribly sad about what I had just witnessed. I felt really strange on the way back home- like I had just glimpsed a completely different, unbelievable world, yet I knew that I would be unable to articulate to everyone back home what it was really like. But, like most humans, I adjusted pretty fast. I made it back to my apartment, snuggled into my own bed, and life went back normal. After a few weeks, it was like I hadn’t gone at all.

Glacier National Park Glacier National Park I was surprised by just how absolutely massive the boat was – there were three bars, two theatres, four hot tubs, two pools, a spa, a gym, and a whole bunch of free restaurants. My bed was magically remade when I entered my room in the evening, with a little chocolate resting on my pillow. Sometimes it felt like being at summer camp, with evening activities led by an animator brimming with fake enthusiasm. When each activity came to a close, the next logical way to pass time was to go back to the buffet. Eating copious amounts of food was a serious, continual event on the cruise, and it felt like being handed the keys to a candy store. When our boat docked in Juneau, I had some time to walk around town by myself. The coastal towns in Alaska are small, packed with tourist shops and tour companies – grizzly viewing, whale watching, ziplines, train rides. Most of the salespeople and tour guides were seasonal workers from out of state. On my walk, I passed bright jewellery stores and tacky souvenir shops. Most of the windows displayed Native-inspired potholders, key chains, tshirts, postcards, every possible cheesy thing. I was looking for something more authentic, a shop with stuff made by local people that were paid fairly for their work. Something more respectful of the culture than cheap make your own moccasin kits and “Alaskan Native friend” dolls with fur trim and big pretty eyes. Uninterested, I kept walking through the crowed, rainy streets. I passed a small community center nestled in the shops. And as I glanced in the window, I saw a packed room of mostly Indigenous folks eating dinner. I noticed the emergency soup kitchen sign in the window. I paused to look around at the town – the village was flooded literally thousands of mostly white, overfed tourists, seeking a souvenir of a frontier fantasy or curio of Native Alaska, and here were a room full of people presumably actually from the area, invisibly eating at a soup kitchen. When the tourist season ends soon, the wealthy shopkeepers will close their doors, the guides will fly back home, and the boats in harbour won’t dump hordes of visitors into the town. I’m pretty sure the soup kitchen will still be open. The next day, the cruise ship was heading up through Glacier National Park, so we were asked to be extra careful not to let litter blow overboard. I contained my inner sarcasm, something about how out of all of the steps we could take to preserve the pristine Arctic, maybe could we please not litter? I felt a surreal disconnect of being on a boat whose sole purpose is to help people over-consume in the name of pleasure, watching melting glaciers calve off into the ocean as hundreds of people stare out windows with their cameras. Literally perpetuating and documenting our demise. Wait, let me take a selfie. I thought to back to the month before, the conversations I had in French with the Haitians I met during my trip. It seemed like it would be kind of funny to the trade situations of one of the rich women on the boat with one of the women I met in the village. It would be hilarious... if it wasn’t so absurd that it’s even possible that two humans living on the same planet can have such diametrically opposite realities. To be on a monstrous cruise boat, the epitome of consumption, grazing our way to a National Park to watch climate change melt the glaciers into the sea – isn’t this the American Dream? I hesitate to say that most of the tourists on the boat are immune to climate change impacts, but we’re definitely insulated. And this is climate injustice. A few weeks ago, I organized a speaking event to bring two speakers to Montreal to talk about the Tar Sands and their impacts on Indigenous communities. Crystal Lameman and Garth Lenz, who came to speak, were incredibly moving, and the event itself was very well attended and a big success. Afterward, the organizing team, speakers, and I headed out for a celebratory dinner. I was exhausted but also very pleased with how everything had gone, and I was looking forward to eating a big poutine and beer and hanging out with my new and old friends. On our way there, amidst thoughtful conversations, we were approached several times by homeless men asking for change in the bitterly cold night. I had been feeling so great and refreshed by the event, but each time they asked me, my heart dropped. I felt like I could do nothing, that I had done nothing, and it was a searing reminder that the work is never, ever done. That no matter how much I or anyone does, no matter the small successes, there is always more to do. And it's often overwhelming and disheartening. My birthday was in October, and when I blew out the candle last year, my wish was to maintain balance. When I get involved in something, whether it's a friend or a project, I tend to give it my all. I'm the friend who will listen to you for hours, I'm the sister who will always proof-read your cover letters, I'm the coworker who will spend the extra hours making something great, I'm the girlfriend who is always supportive. I tend to do something all the way; I give it my whole heart. I've learned lately that this is one of my best qualities, but it's also the most dangerous for myself. I've been trying to find the balance of how to care deeply for people and projects and places that are impermanent, how to give so much but still keep some for myself.  Last year, I struggled with balancing my multiple part-time jobs, a relationship, my climate justice volunteer work, and spending time with friends, family, a needy cat. I've gotten much better at it these past few months, and although most of the time things seem under control, sometimes I still feel like I'm pulled in too many directions, and I'm not sure where the source of this energy is coming from. Over the summer, I bought this beautiful poster by the Beehive Collective that says "For the long haul", which I framed and put on my wall as a reminder to pace myself. I can't save everything by tomorrow, I can't save everything in a year, and I'm not even entirely sure I can save anything ever. I've been incredibly lucky in my life to have so much privilege and purpose for living. But I find it hard to have an endless source of positive energy. Sometimes it feels so difficult to feel optimistic, to wake up every and keep fighting, to care so deeply for people and places that I will inevitably lose. Sometimes it feels that I am putting so much of myself into people or projects that I love, and they end up breaking my heart. Some days I find myself angry - angry about oppression, angry about racism, sexism, homophobia that I see around me almost every day, and what's perhaps increasingly more frustrating is not the overt oppression that most of us would readily recognize, but the millions of small ways that we keep the hetero-normative, white patriarchy systems in place, the systems that are built to keep things the way they are. I become frustrated with my ability to explain these issues to people who haven't been exposed to them before, especially in French. I become frustrated with being frustrated itself, since I feel that being an angry activist is alienating to others, isn't a good way to engage people, and also it just feels shitty to be angry and offended all of the time. Where can I find the strength? For some people, that strength comes from community or a partner or family, and certainly some of my strength comes from that as well. But I think for me, a lot of that strength comes from the land. From standing quietly in the forest when it's snowing, with hardly any sound except the beating of my own heart. From discovering a track or a flower. From catching a glimpse of a deer running away from me, which reminds me that all of my actions have repercussions. From watching the bees in my hive bring in pollen, dancing for their sisters to show them the way. From the pride and awe in observing a seed that I planted grow into a carrot that I plucked from the earth to feed myself. Those moments have always seemed so heavy with meaning, but I find them so far away in the city. I live downtown: instead of owls and coyotes calling to me from autumn open windows, I fall asleep to sirens and snow plow trucks and drunk people screaming outside my window. My attempts at indoor gardening end in my cat knocking dirt all over the table. I walk to work enviously looking up at the mountain, torn between escaping and making a living at my sustainability job. Maybe all of this writing means that I just need to escape to the cottage again, that I need to spend more quiet time outside. I'm insanely lucky to have grown up with acres and acres to safely explore, and weekends at my cottage for sure at times is the only thing that keeps me sane. When I leave the land on Sunday evenings to head back to the city, I make my feet leave, get in the car, but my heart stays. In some twisted way, the only way to save the land I love is by leaving it. For now, all of my work and friends and community are in the city. To fight the pipeline that threatens my riverbank, to fight climate change which threatens my forest, to learn the skills to fight well and fight forever, I need to be here. When I get back to the mountains, it takes some time to quiet my mind. But soon, my thoughts slow, I notice more around me, it's easier to stay still. I feel reconnected, and I know that I can keep going. And sometimes, if I'm being honest, sometimes when I'm at the riverbank all alone, I whisper, "Thank you. It's all for you."  Two years ago, I got a motion sensor camera that attaches to a tree and takes photos of animals that walk by. It's the best! It's so fun to check on the camera at my cottage every few weeks and see what has been in the area. I move it around from time to time, trying to find the most active areas. I've seen tons of deer, turkeys, some coyotes, foxes, ducks, an otter, a mink, a fisher, and beavers. Especially this past fall, there were so many apples thanks to the extra beehives I have. The deer love those apples. I'm still waiting to get a bear or (way less likely) a cougar! It’s an autumn evening, so still except for the crickets and the apples dropping nearby. My bees pollinated so many trees this year that there are more apples than I’ve ever seen at my cottage. So many apples that my brother and I pressed them into apple cider, and I made liters of applesauce. Today I started fixing up the three hives, making sure they had enough food for the winter. My parents left for the evening, so I did last one weeding of my garden, watching flocks of Canada geese and blackbirds pass overhead. I harvested the last of the carrots, and admired the dirt under my fingernails.

Satisfied with my TinyHomestead chores complete, I walked down by to river, in my deerskin moccasins, munching on my very fresh little carrots. I noticed deer tracks, scared away a ruffed grouse. Avoiding the poison ivy, I crouched in the grass and peered down to the riverbank. Raccoon tracks covered the mud. Hey, a heron was here yesterday. A beaver weaved close to me and then smashed its tail into the water, trying to scare me away. It took me a while to be able to enjoy the river again, to be able to sit on the bench and watch fish ripple the water without feeling sadness. Or despair. I realized today that it’s been almost a year since I’ve been involved with tar sands and pipelines issues. I remembered how it felt to realize that a decades old pipeline was lying a few miles up the river that I have loved my whole life. I feverishly researched more and more, and I was devastated to find out that it had a history of spills, and was slated to reverse its direction to take diluted bitumen from the tar sands to Portland, Maine. It was called the Portland-Montreal pipeline- PMPL. To get to my cottage from the city, we have to drive through town, crossing over the shaved strip where the pipeline snakes underground. I try to avoid noticing it sometimes, but the yellow markers where it crosses the road and the sign asking “Mayflower, Kalamazoo...Sutton. For who?” nailed up by citizens, which referenced major oil spills with similar pipelines as the one a few feet away always reminded me of it. There’s this scene in the documentary Gasland that I feel sometimes. There’s a part where Josh Fox says something about seeing fracking wells everywhere he went, how everywhere felt like Gasland eventually. I felt betrayed, somehow, when I realized that this whole time that I thought that the land that my family had was safe- from pollution, from destruction, from reality I guess, but really there was a pipeline there this whole time. A few months ago, I went to Toronto for a weekend. On a walk on a beautiful summer evening with a person I was quickly falling for, I realized that Line 9 crossed the river close to where we passed. I felt I couldn’t escape – pipelines, or trains carrying oil, or trucks carrying oil - are everywhere. The city was full of noise and people and waste, but coming to the country just made me sad that this place was in danger too. Last night when I was driving up here on one of the country road, I passed two girls obviously lost in the dark, with their bikes. “Where you guys going?” I asked. “Oh, Glen Sutton, our dad has a place on the river”. “What color is his house? Green?” “Yeah! ...how’d you know?” “I’m headed right by there, I think can see your place from mine. Does your dad go kayaking a lot? He has a beard?” “Yeah! So it’s your place that has the bench by the water?” The bench by the water, where I’ve spent so many hours, watching for beavers, kingfishers, hoping to see the otter. I saw them on the other side of the river drive by with their dad this evening; they rolled down the window and we yelled out some conversation across the water. When they passed, I was left with myself and the crickets again. I wondered - do I feel hopeful about this river? Will the banks stay clean, the beavers and the otter say oil-free? The National Energy Board public hearing for the Line 9 project is in two weeks – Line 9 would eventually supply tar sands oil to the pipeline a couple miles upstream from me. How do I feel, a year after working on this pipeline and the two other pipelines that pass through Montreal? I’m not sure. It’s hard to tell, standing on the banks. The river seems oblivious to danger – from people, from climate change, from oil spills. It’s just doing what it’s doing, as it’s done, and as it will. On this quiet evening when everything is enjoying the last summery days, it seems strange to think that this place could be destroyed, kind of unfathomable to think that one day I could come here to an oil-soaked bank. But maybe. Probably Enbridge’s Line 9b will get reversed in the next few months, and TransCanada is trying to build the Energy East pipeline, even bigger than Keystone XL, across Quebec to New Brunswick to export. Then maybe this pipeline will get reversed too, filling this decrepit pipe with filthy tar sands oil. I’ve spent so many hours in meetings, reading a bazillion emails, talking to people about – how do we stop this? And not just this, but all of them? Sometimes it feels like we’ll win, and sometimes it feels like it’s pointless. Why do we see destruction as progress? Shouldn’t life for people and all living things be getting better, not worse? But out of everything, I feel grateful for the people I’ve met through this fight. I felt so alone when I first learned about my river being in danger. Like there was nothing I could do to stop it, that maybe nothing could. Over the months, I’ve made so many good friends, heard so many interesting people’s stories, felt so unified with people. The oil companies have done more to build a community for me than anything else could have, and I guess I have to thank them for that. I've had the craziest year and a half. I would say the craziness started when I finally became employed full time in my field. I was super psyched to be working on really exciting projects, projects that could really change how universities operated and how they incorporated sustainability into their operations. Unfortunately, it meant that I had three part time jobs which somehow together added up to about 40 hours a week (and I didn't take lunch breaks).

At first, I found it a little challenging to juggle so many things. This meant that I had three work email accounts, which I had to check every day (often I checked them on weekends - I couldn't help myself) and answer time-sensitive emails even if it wasn't on the day that I was supposed working at that place. You can see how this is already a little hard to keep track of. It meant that I had four bosses (one job had two supervisors), a ton of really great coworkers (I won't even try to count how many), and received about 50 emails a day between all of the work accounts. Since I was managing projects and teaching, I tended to have a lot of responsibilities, and I had to fix problems. I love problem solving. But there were always problems that needed solving. I tended to still think about them when I was watching tv, when I was showering, when I was drifting off to sleep, when I was a romantic dinner with my partner - I couldn't stop thinking about these problems, even when I tried to stop. Because I worked three part-time contracts, I had no paid vacation, no sick days, no paid lunch breaks (so therefore I didn't take lunch breaks - it meant I would have to work longer in the afternoon), and I often had evening meetings since I work with student groups. Sometimes I would have to leave one job and walk a few blocks to my other job for an important meeting, then go back to the first job (although I really tried to avoid this - it was insanely confusing for my brain). Most of my friends are also pretty busy, but when people would say "we need to hang out, Shona!", I'd be like "yeah! Uh...let me whip out my agenda. I have an hour next Tuesday between 4:30 and 5:30. Then I have meetings and plans the rest of the week, then I'm going to the cottage on the weekend...how about the week after?" I wouldn't even try to remember my schedule; it was so confusing that I needed my agenda open at all times. As the months progressed, I felt myself turning into a caricature of a girl who was insanely busy, rushing from one university to another with her notebook, her agenda, and a cup of tea (usually in a mason jar, but always a cup of tea. Caffeinated.). I asked my partner to draw me a picture of this caricature. All of the days kind of blended together and I had a really hard time keeping things straight. I was super busy, super stressed, but I was doing good work! I was working on things that I cared about, projects that I genuinely loved. After years of working jobs that I was less than thrilled about, it felt amazing to get paid to make the world better. I wrote a Sustainable Event Guide, taught some wonderful and inquisitive students about environmental science, and worked with a great team of 40 McGill students to assess a heritage building and make a 5 year Sustainability Action Plan. I think somewhere in there I also fit in starting a business, tweeted, went to yoga, canned food for the winter, kept some beehives, gardened, and went to the cottage every two weeks (this is the only thing that kept me sane). Also I had friends, family, a cat, and a partner which needed or wanted various amounts of time, mostly which I was unable to give because I couldn't justify spending time on "fun" things when there was important work to be done. You can see me slipping off the classic activism burnout cliff. Then, somewhere in November, I realized that the Montreal - Portland pipeline reversal was going to be happening a few miles away from my cottage. I suddenly felt my home, the only place I really had an attachment to, was under attack from an inevitable future oil spill. I had to do something; there was no way I could sit back and wait this fight out, it was too important to me. Somehow, I would make this fit into my schedule. I knew that I couldn't keep up this level of intense working and activism - my brain felt constantly fried, I would tell the same people the same anecdotes because I couldn't remember who I told them to, or I would completely forget what other people told me. I could hardly relax, let alone sit still for an hour and a half to watch a movie without constantly checking facebook or attending to some "crisis". I knew I had to cut things out of my life, but I couldn't see what I could simplify. Everything was too important. Instead of delegating tasks or asking people in my life to help me out, I felt that I could or should somehow take on more work. This doesn't make sense, and I know coworkers would have happily taken over certain tasks; my partner would have quite easily done the grocery shopping instead of me. But the more productive I was, the more I felt anxious and the urge to be even more productive. I got such a sense of pride and high off accomplishments, and the stress made me feel that I was doing essential work. I felt guilty if I had an afternoon of being unproductive. I could tell that people wondered how I did it, but the fact that I did keep it together for so long was also a source of pride for me - yeah, I'm working on all these cool projects, I'm pretty organized, I'm hyper-productive, I have a million different things going on, and I still sleep 8 hours and eat three times a day. Meetings with other activists often incorporated kind of a subtle bragging of who was the busiest, who was the most overwhelmed or productive. Instead of realizing that this is actually kind of unhealthy to glorify being a workaholic, I finally felt that these people understood me. At some point, I realized that my relationships were deteriorating. I didn't really have time for friends, and often they didn't have time for me either. I wanted to spend more time with my family, but I was way too busy. I knew my partner, although very supportive and understanding of my three job situation, was becoming resentful of my lack of time and emotional availability. But I knew it wasn't forever - one day, I would get this illustrious full time job with dental insurance and paid vacation. It would pay off. And then, my job contracts were all slated to end by the end of May. There was finally a way out, to wrap up projects and courses without having to leave before they were completed. Around this time, I also got into a car accident, got my wisdom teeth pulled out, went through some relationship changes, and moved. These were all pretty tough to deal with. Instead of reaching out to others, I kind of just kept it in. I crashed pretty hard at one point. But then I realized that I was extremely fortunate to have friends and family that were there for me, if I would get over my pride and just ask for help. I finally felt like it was okay to rely on other people, that I didn't have to do everything. This probably seems super obvious, but after months and months of feeling like I was the one who had to keep everything together, at work, at home, I realized that things would be okay if I took a step back. And they were fine. At first, when my work hours dropped from 50 (since I was also doing about 10 unpaid hours a week with Climate Justice Montreal stuff in an attempt to stop the pipelines) to 20 during the summer, I didn't know what to do. I knew I was in a transitional stage, I knew I should be looking for more employment since working full time is what one is "supposed" to do. What was I supposed to be working on? What projects was I supposed to be doing, how was I supposed to fill every minute of my day? I didn't know. I felt super lost. But as the days went by, I rejoined the gym (I finally ran up the top of Mount Royal!), I hung out with friends in the park, I reconnected with some friends I hadn't seen in a while, I actually read a book and watched some movies, I spent more time outside, I listened to music. I didn't really have a schedule outside of my work week, I did whatever I felt like. These were all "unproductive" things. And they felt amazing. I know soon I'll be ready to jump back into things, but it is only with these past few weeks of doing "nothing" that has given me perspective. It's not normal to work 50 hours a week. It's not normal to feel hyper stressed and overwhelmed all the time. And if these things are normal, they shouldn't be. So why share all of this? It's not flattering. Although I had heard about activism burnout before, I didn't feel like it applied to me. I was fine, I could keep being super productive without crashing. And if I felt like it didn't apply to me, I'm sure there are other activists or passionate people who also feel like they're fine, they can keep on going. But something I can realize only now is that it's okay to say no. It's okay to say "sorry, I would love to, but I totally don't have time." or "Hey, can you do me a favour please?'. It's okay not to work full time; it's okay not to work at all. Although I try not to follow convention or social norms just because they're there, I did definitely feel pressure to be this person who had their life together, worked full time, was on a path to "success." I kind of let other people's vision of success pull me away from my happiness. So, it's okay. I know there are a whole lot of bad things going on with the world - more and more every day, it seems - and you're going to help fix it. That's awesome- we need so many intelligent, passionate people who care enough to do something. But the key word is help. Help fix things. Not just you. We'll be okay if you relax for a little bit, play with your dog, go to the movies. We'll be here when you come back, and then you can take over when we need to take a break. Maybe this is a better way of fighting. My bees survived the winter, luckily! I had wrapped them in sheets of thick styrofoam and geotextile and made sure they were full of honey and pollen so they had enough food for the winter. I guess it paid off, since both hives were fairly strong as spring emerged. I started with two hives, and I had named them based on their collective temperament - Rose is the one on the left since it's a stronger colony and also a bit more aggressive. Daphne is on the right since the queen is less productive, so there are less bees, and they're more docile. Rose was the only one that produced enough honey last year for me to harvest (Daphne was a little slow getting off the ground), so I was expecting that it would continue to be pretty productive this year. When I say "productive", I mean that the queen lays a lot of eggs, so there are more worker bees, which means more worker bees make more honey. If I was keeping hives to make money or to have all of the honey I could possibly use, I would replace my less productive hive with a new queen so that I could harvest honey from both hives. But my nerdy biology goal is to raise bees that are adapted to my area, by splitting the strong hives as they grow and letting them make their own queen instead of continuously buying queens from a breeder, as most people do. It's a bit more risky to let the bees make their own queen, since then it needs to mate with males in the area (instead of coming inseminated already, as is when you buy them from a breeder), and it can get killed when it leaves the hive for this mating mission.  So over the weekend, I built a third hive. I'm not very mechanically minded so this actually took me a few hours to hammer all of the pieces together and paint them. Once it was all set up and the linseed oil I used was dry (I use linseed oil because it's less toxic than paint), I transferred a few frames from the strong hive into the new hive. Usually people put four or five frames from the old hive into the new hive, and those frames need to include honey (to give the new colony extra food if they need it), capped brood and eggs (developing worker bees so the population is continually replenished), adult worker bees, and a new queen cell. By chance, I found that the bees had been growing a new queen in a queen cell for their strong hive, which is a sign that they would have swarmed. Swarming is when the hive is too full or small for everyone, so the queen and a cluster of worker bees take off to start a new home, leaving more room for the new queen and rest of the workers. Once I put five frames from the Rose hive into the new hive (still trying to figure out a name for the new one), I added empty frames to make sure the hive was full, then I closed the lid. This is my first time splitting a colony, so I kind of saw it as an experiment - we'll see if it works!

A few weeks ago, some of us working on the Line 9 pipeline issue in Montreal headed down to Portland, Maine. Line 9 currently goes from Sarnia to a refinery in the east end of Montreal, and currently flows east to west. In November, Enbridge applied to the National Energy Board to increase the barrels per day capacity and to reverse the flow from west to east to accommodate oil from the tar sands. Although the initial plan to also reverse the Montreal Portland Pipeline from Montreal to Portland was defeated in 2008, it has resurfaced recently. The problem with this heavy crude (or diluted bitumen) is that it's so viscous that they have to add toxic chemicals to get it to flow through the pipes. Besides the fact that the tar sands will basically undo any changes Canadians do to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, this diluted bitumen is especially gross when it leaks since the oil sinks in the water and the chemicals (known carcinogens) evaporate in the air and can be smelled from miles away. How do we know this will happen? It's already happened with a massive spill in Michigan and more recently, Arkansas, where the pipeline was very similar to the existing line from Montreal to Maine. On our way back from Portland to Montreal, we decided to follow the pipeline route (which you can see here). And what we found shocked me. But first, we stopped at the Cape Elizabeth lighthouse, just a few miles outside Portland. After watching the huge waves for a while, we started our 7 hour trip back to Montreal. I was told that I wouldn't believe our first stop - the "tank farm" where energy companies store oil in huge silos before transporting it to the Portland Pier 2. We had trouble finding Hill Street where Portland Montreal Pipeline's tank farm is located, but when we did, I couldn't believe it was real.  There were tanks full of oil - right in a residential area in South Portland. The whole neighbourhood reeked of gasoline, like there was an open can of gas in front of me. I couldn't believe that seemingly normal looking houses were yards away from giant oil tanks. I think I went white when I saw a kids' playground right on the other side of the fence. How could South Portland stand for this? It might help that Portland Montreal Pipeline Limited bought the town a library.  Thoroughly shaken, we drove northwards up through Raymond to get lunch. We stopped at a super cute and delicious deli that...the pipeline almost literally ran right through. We continued on through Casco, Waterford, and Bethel which passed municipal resolutions against tar sands oil flowing through the pipeline in their towns. And also where 1,900 litres of oil spilled from the pipeline in 1990. The road crossed into New Hampshire, where we drove past the Shelburne Pumping Station, just yards away from the Androscoggin River. It's an important river for fishing and tourism in the area that provides drinking water to people, and the pipeline crosses under the water twice. We passed Randolf, New Hampire, which is the first place that the Portland Montreal PipeLine company showed up for a public meeting in November. Not far past the pumping station, we passed areas in Vermont that have previously had oil spills due to corrosion or natural forces. Close to the spillage areas, the pipeline crosses the Connecticut River, the largest and longest river in New England. One of our last stops was the Highwater Pumping Station right on the border of Quebec and Vermont. It's on the Quebec side, so it's strange that some of the signs are only in English. The BB gun holes in the nearby signs were a little disconcerting too.  On the way back to Montreal, we passed the pipeline crossing through the town of Sutton, just a few miles from my family's cottage. My trip ended at the cottage, where my dad was busy making maple syrup. The next morning, I headed down to the river, where we've seen otters, mink, and beavers.  I have spent so many happy days by this river, mesmerized by the splendour of nature around me. There are oil spills around the country every other day, and it breaks my heart to think of the pipeline taking this place too. |

About ShonaI'm an eco-conscious girl from Montreal, Quebec. I'm currently an adjunct science professor at Champlain College of Vermont (Montreal Campus). I'm interested in any opportunities to expand my experience with grassroots activism, climate change legislation, or environmental education. Archives

March 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed